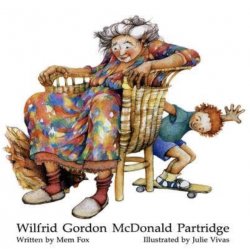

Storyline Online Again Willfrid Gordon Mcdonald Partridge

Gareth B. Matthews

Review of Wilfred Gordon McDonald Partridge by Mem Play a joke on (New York: Kane Miller, 1985). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 8(3): 1.

Wilfred Gordon McDonald Partridge was a very pocket-size boy with a very big name. He lived next to an old people'southward dwelling, where he liked to go and socialize with the eccentric old people he found there. Mrs. Jordan played the organ for him, Mr. Hosking told him scary stories, Mr. Tippett, who was himself crazy about cricket, played with him, he ran errands for Miss Mitchell and advertizingmired the giant voice of Mr. Drysdale. Merely his favorite person of all was Miss Nancy, to whom he told all his secrets. One day Wilfrid Gordon overheard his mother and father say that Miss Nancy, who was 96, had lost her memory.

"What's a retentiveness?" asked Wilfrid Gordon.

"It's something you lot remember," his male parent told him. Dissatisfied, Wilfrid Gordon began to ask the old people in the domicile what a retention is.

"Something warm;" said Mrs. Hashemite kingdom of jordan.

"Something from long ago;" said Mr.Hosking.

"Something that makes you cry," said Mr. Tippett.

"Something that makes you lot express mirth;" said Miss Mitchell.

"Something every bit precious equally gold;" said Mr. Drysdale.

Wilfrid Gordon went back home to look for memories. In a basket he collected: shells he had put in a shoebox, a puppet on strings, a medal his grandfather had given him, his football, and a overnice warm egg, fresh from under the hen.

Wilfrid Gordon took his handbasket of precious objects to Miss Nancy, who was in deed very pleased. As Wilfrid Gordon took each precious thing out of the basket and gave information technology to Miss Nancy, she remembered something. The warm egg reminded her of eggs she had once found in a bird'south nest in her aunt's garden. She put a shell to her ear and remembered going to the beach past tram long ago, in button-upwards shoes. She touched the medal and remembered sadly her big brother, who had never come dorsum from the war. The puppet on strings re minded her of a puppet she had once shown to her sis. The football reminded her of the twenty-four hours she had first met Wilfrid Gordon. With these memories fresh in her mind, Miss Nancy had her memory dorsum again.

Similar Proust's memories of childhood, our ain memories are sometimes locked in the precious objects of the globe, waiting to be unlocked by a taste, a glance or a touch. In a sensory deprived surroundings-a hospital, say, or a nursing dwelling house-memories may fade, and with them, retentiveness.

Of form, organic deterioration, or physical or psychological trauma, may play the leading part in the loss of memory. I once phoned long-distance a friend I hadn't seen in xv years. I wanted to denote that I was about to fly to the metropolis where he was and so residing, and I wanted to see him.

The voice on the other stop of the telephone was familiar enough. I gave my proper noun and waited for an expression of recognition and pleasure. None came. There was only silence. Feeling increasingly uncomfortable, I began recalling some of the experiences nosotros had enjoyed together. In that location was still no response. Yet the voice was friendly. I was invited to visit.

I went. The figure I encountered was what I expected-a niggling older than I remembered, but with the familiar confront, voice and gestures. Withal at no time during the evening we spent together did I receive whatever recognition of our common feel together. The person I socialized uneasily with that evening was either unable or unwilling to dredge up the memories that, according to John Locke, are both necessary and sufficient to brand him the person I had once known so well.

Locke's views on personal identity (run into his An Essay Concerning Human Nether standing, Volume 2, Chapter 27), though they harbor many difficulties familiar to all serious students of the subject, retain a natural entreatment. On Locke's view, Wilfrid Gordon is non just using his collection of precious objects to assistance Miss Nancy to accept sure experiences-some of them warm and comforting, others lamentable or funny. He is helping her to be able to make connectedness with the past in such a way every bit to exist the person who waved cheerio to her large brother as he went off to state of war, and to be the person who first met the footling boy with a large football and a very long name on the porch of the old people'due south home some months before.

It is difficult to spend fourth dimension with a favorite old person, as Wilfrid Gordon did, and not puzzle over personal identity. Merely equally one may have lost forever the person one cherishes, a precious object may bring her dorsum again, perhaps with a force that removes all uncertainty she is still at that place.

Source: https://www.montclair.edu/iapc/review-wilfred-gordon-mcdonald-partridge/

0 Response to "Storyline Online Again Willfrid Gordon Mcdonald Partridge"

Post a Comment